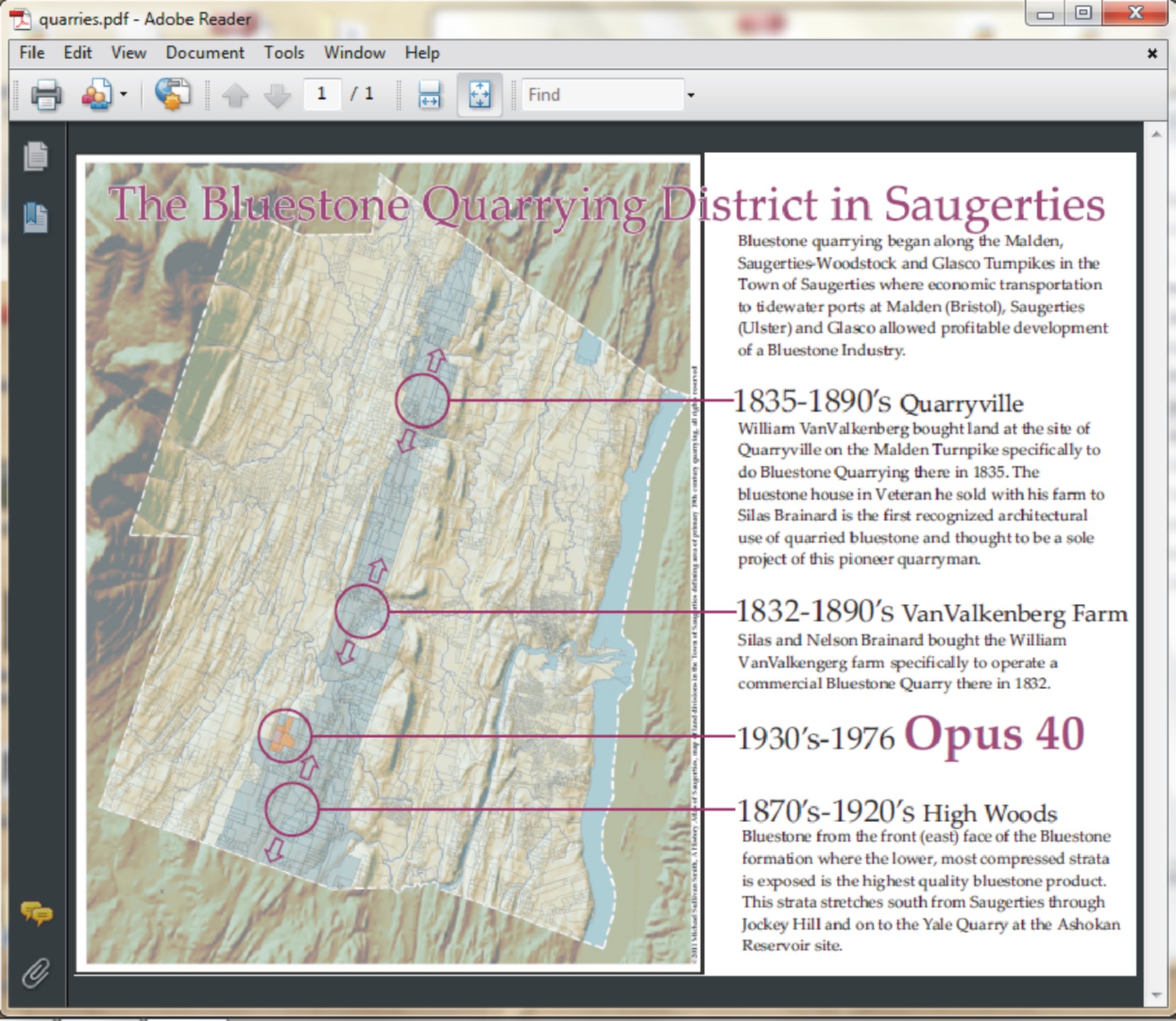

The blue down the center of the map is the highest quality glacial-carved Devonian sandstone to be found. The earliest commercial quarries for sidewalks, steps, window lintels and sills, and carved architectural ornaments made of this bluestone were started here.

The exposure of the bluestone found in this blue area is the bottom and most dense part of a deposit that continues under the Catskill mountains and doesn't surface again until it reaches Ohio.

On this map the shading of the drawing to the right of the blue line is a common flaky shale and the deep shaded area along the left edge of the picture; the Catskill Escarpment; becomes an even less dence mud rock further up its heights. All the land of Saugerties between these two indescript formations is riddled with 19th century bluestone quarry pits and rubble piles.

Opus 40 occupies one of these quarries and is made from the fragments of waste stone left when the slabs were taken from the earth and shaped into the products that drove the country economy of Saugerties for nearly a century.

Below the PDF is a composition that covers the history of bluestone from its birth nearly 400,000,000 years ago to its present prominance as the material of Opus 40.

This page has been created to describe the quarry aspect of my Great Knot site-specific sculpture. It deals with the material used to build it and the reason that material is available. There are many other aspects to this environment and each one will be covered in a page like this.

A deeper awareness of the material and the intangible environment is the purpose of creating a site-specific work. The sculpture is as much about all the aspects of nature and humanity in this environment as it is about the way the art appears.

This is a web production of Michael Sullivan Smith. It's distributed free of commercial or government platforms from the Cloud. If you find it informative you may be a patron by visiting the Patreon.com link on this introduction page. There you will find a list of interesting creations such as this to add to your electronic collection.The file burns a lot of bandwidth every time it is pulled down from the cloud. Patrons help me pay for this service so that you can save this file from the cloud into your computer. The PDF from this streaming file can be downloaded to your computer. The only good thing to come out of commercial dominance of the Internet is the power it needed in your personal computer to pull off this dominance. Please use what you have and save energy. Save the PDF to your computer if you're going to study this file.

The Life of Bluestone

|

Our planet is a creative force. It continually makes new things. It mixes and molds, formulates and blends. It's been doing this for billions of years.

Some of these creations are sensuous, ever changing experiments of light, texture, sound and aroma. We and all "living" things around us are part of this ephemeral side of the earth’s creativity.

A more permanent side to our planet's creativity it reserves for the composition of its essential form: rock.

Through a unique combination of both its ephemeral and permanent sides we have bluestone.

Many eons ago our planet directed its sensual side to the earliest attempt at what was ultimately its greatest creation: the forest. This, like all youthful experiments, was flamboyant; volatile in composition. It was a forest with an explosive, fiery life cycle. Over millions of years this experiment continually blended the ashes of the forest's seasons with the rains of an atmosphere saturated in an acrid haze, eroding the scorched fragments of rock at its base to be deposited as sands in the depths of a broad sea.

At the end of the forest experiment a dead land, no longer held by the forest's roots, washed down to cover these scorched sands. After tens-of-millions of years a two mile thick layer compressed the sands at the bottom of a deep sea. Heat from this pressure and the depths worked upon the sand’s scorched and crystalline elements, chemically merging them with properties of the limestone bed of the ancient sea. The result became the massive 500 foot thick monolithic plate of dense dark sandstone we know as bluestone. This process of its birth yielded an organic bonding and color that makes bluestone a product of nature that is incomparable and in a way mysterious.

Over the next hundreds of millions of years this plate was lifted from the depths under the drifting action of the Appalachian and Acadian land masses. Unable to push this bluestone plate and its two-mile thick burden forward, they pressed under instead, eventually forcing this land mass three miles high at its eastern front. Over millions of years of exposure this mountain eroded west to make the continental plateau and east down the Hudson River. In time the easterly edge of the ancient bluestone plate became exposed along the west side of the Hudson Valley.

In the most recent hundred thousand years man appeared, at first hunting the animals that sheltered beneath the broad overhangs of the bluestone ledges that followed evenly spaced stress fractures made as the weight of the mountain was released. Over a hundred or more generations man settled in to cultivate the rich soil of a sweeping savannah deposited in a valley by runoff from the waters draining from these high ledges.

In his long union with these ledges man developed a spiritual connection with their plated structure. They represented a symbol of the Earth which he likened to the form of the shell of the turtle. He lived in harmony with this symbol. He was a life this turtle bore on its back. The other life forms there were what the earth gave him to fill his needs. He moved not one stone from these ageless ledges lest that harmony be disturbed.

Four hundred years ago Henry Hudson met these native peoples. In recording the resources he found on their lands he wrote of the "great store of slate for houses, and other good stones". Within a score of years stone houses began to be built by the Dutch settlers from "cliff stone", the dimensional fragments fallen to the base of these ledges, and at the same time the native people, the Warranawonkongs, disappeared.

Two centuries later bluestone cliff stone became an industry with its quarrying and finishing into perfectly dimensioned stone slabs growning to involve over half the land mass between the Hudson river and the Catskill mountains.

Before modern man arrived only the earth had the power to change the landform of this region. For thousands of years the native inhabitants lived as an integral part of this land and left no permanent marker that may disrespect it. The first Europeans to replace them used this land's stone to raise themselves above the earth, using it for a personal sense of permanence. This permanence of their stone foundations and their stone houses is now the “landmarks” of their era.

|

This was known as North River Bluestone after its shipping location on the North (Hudson) River. In this century of extraction and movement bluestone's geological formation underwent the most rapid mass distribution of a landscape element ever to take place in the history of the Earth. One can stand on the native land of Saugerties where the commercial quarrying began on a sidewalk in Havana, Cuba.

The landmarks of this era are the large mounds of “quarry rubble” that mark the permanent change this landscape underwent. Over the course of their operations the quarries cut away thousands of acres of bluestone ledges down as much as a hundred feet. By the time bluestone quarrying had ceased to be an industry it had left millions of tons and billions of pieces of rubble accumulated when the top burden, unmarketable breaks, chips from finishing and blasted fragments were stacked in piles the size of small hills. Along with their abandoned quarry pits whose angular cuts and smooth surfaces have left hundreds of clean edged depressions, bluestone has left a lasting impression on the land.

All this acreage of abandoned quarries, barren rock heaps and broad exposures of bedrock has no practical use. A residence cannot satisfy the drainage requirements of the health code and nothing of use can be grown on them as open spaces.

They do have cultural value, though, as a window into the history of the planet. Each quarry face forms a unique slice of the strata that eventually compressed into the bluestone plate upon which most of the east continental plateau of the United States resides. This is not approachable anywhere else but in these quarries cut into ancient exposures of the Hudson Valley.

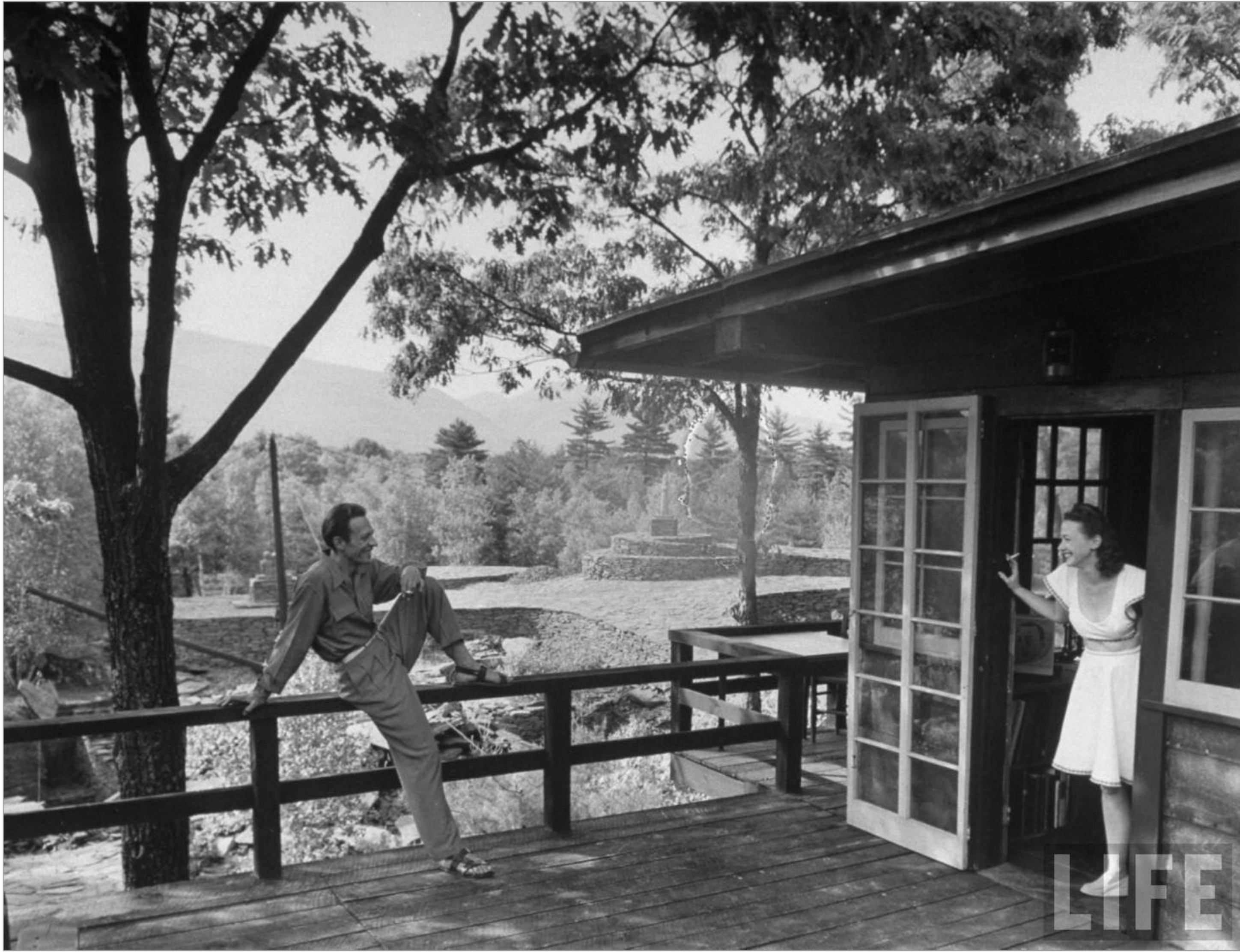

Opus 40 is a well-recognized landmark and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Its creator died while working on his sculpture, making both him and the 40-year time span of his work the stuff of legend.

An architectural use was why the quarrymen wrested bluestone from this bedrock and finished it to precise dimensions. Most of the site's cast-offs at Harvey Fite's disposal were remnants of this craft. In this Opus 40 echos the millions of crafted pieces produced by these quarrymen that now lie thousands of miles away in century-old structures and public spaces. Opus 40 tells of a reach of bluestone far beyond the locale of its origins in the way it has itself been universalized as an artwork icon.

Bluestone is a resource easily accessed for creating environmental sculptures. All over this region hundreds of quarries and their rubble piles each have unique transcendent characters to inspire art. The touchstone for encouragement is alive at Opus 40.

Thousands of acres of ancient quarries are the full canvas upon which refined site-specific quarry-based works wait to be created. The bluestone exerts a powerful draw on sculptors and their personal creative visions for this ancient material and its heritage setting. The stone and its bond to a specific social, cultural and geographic environment has become medium.

|

Opus 40, the environmental sculpture of Harvey Fite, is an innovative use of this quarrying heritage for creating a significant work of art. It transforms the site of an abandoned quarry into a new identity as part of the landscape.

Opus 40, the environmental sculpture of Harvey Fite, is an innovative use of this quarrying heritage for creating a significant work of art. It transforms the site of an abandoned quarry into a new identity as part of the landscape. Opus 40's structure is influenced by Harvey Fite's travels in South America and his work with the monumental ruins at Copan. His craft applies the age-old architectural methods of building with the stone.

Opus 40's structure is influenced by Harvey Fite's travels in South America and his work with the monumental ruins at Copan. His craft applies the age-old architectural methods of building with the stone.