|

the land |

|

|

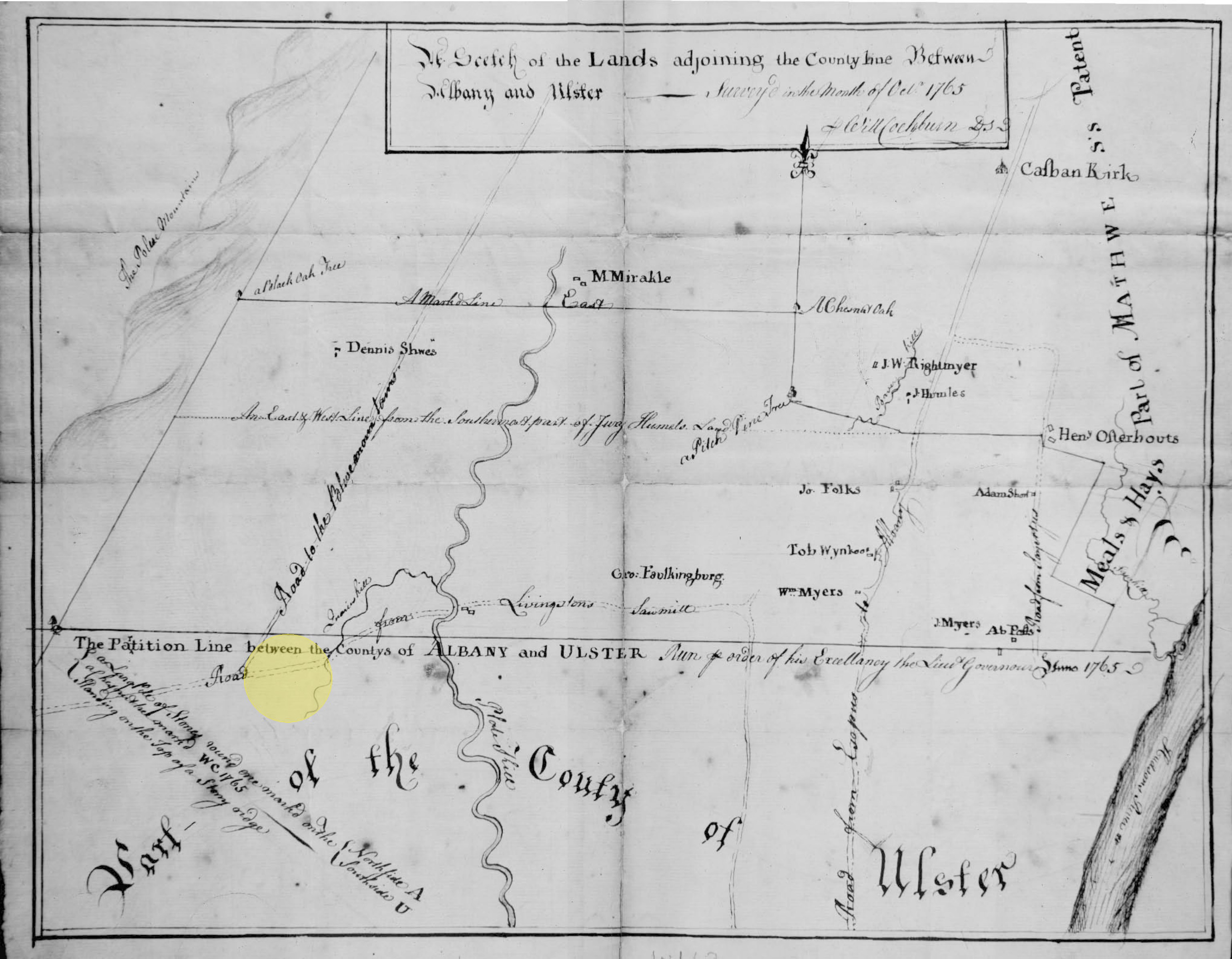

Above (top left): Pre-Revolution boundaries of the greater Great Knot heritage region (link to plate with history of the creation of the Corporation of Kingston) |

fitting the Great Knot into history |

|

In later times, after the Revolution, the stream that runs through the Great Knot was known by the name “Fly Kill”, sometimes “Wilderkill”, after its swift currents that often encroached on the narrow passageway it shared with a westbound foot path, then turnpike road, through a cut in a long barrier ridge.

The "Flykill" name is preserved in the 1781 lease from the trustees of the Corporation of Kingston to William Cassel where its waterfall is a landmark for creating the land's boundary measurements. The wagon road is another reference. With this document begins the sense of the historical environment of this curious quarry and its stacks of rubble that the waterfall rested within, and the stream struggled through, when the Great Knot began to become the identity of this place.

This waterfall has long been a landmark from when Indian and early settler foot traffic gave way to wagons that passed it. Stone loosened from the ridge by eons of churning water's freezing mists was removed, and the stream's natural cut through the ridge broadened, bringing to its stream its first name of “Quarry Kill”. This is the name given it on this earliest survey known to make a record of this region, done in 1765.

|

This hint of the industrious activity of a quarry was a welcome presence in the wild frontier and cultivation spread early along the upper and lower banks of the waterfall's stream.

The greater land offers a lacework of watercourses with similar histories. Colonial roads followed streams because their flow followed a path of least resistance. Settlement followed the roads where building stone for dwellings and meadows for grazing appeared along these stream banks.

No one course of events took place without being example to another. Stone houses, cattle herding, cultivation of winter fodder, quarries, and water powered mills found themselves the signature signs of colonial settlement.

This ancient landmark is known locally today as the “S-curve” where the road must maneuver between the ridge on the north and the waterfall of the Great Knot site on the south. It's a dangerous place on a highway and the many accidents that have happened make it a cautionary landmark now. The waterfall and its quarry faces are seldom noticed and the stream is generally unseen today as attention is paid to the dangers of the road. |

The Great Knot, April 27, 2011  Michael Sullivan Smith, 2015 Click on animation to open parent web site greatknot.com in new browser window |